New to this series? Read The Bromacker Fossil Project Part I, Part II, and Part III.

This post will be the first of a series focusing on notable fossil animals discovered in the Bromacker quarry. I selected Diadectes absitus, a member of the ancient group Diadectomorpha, to present first because, had it not been discovered in the first year of the collaborative field work, the project might not have continued.

Dave Berman and his colleague Stuart Sumida (California State University, San Bernardino) joined Thomas Martens for five weeks of field work in the summer of 1993. They dug a quarry over six feet deep in their search for fossils, while working in a mix of hot and humid or near freezing temperatures, with plenty of rain. It wasn’t until the second-to-last day of the field season that the Diadectes specimen was discovered. By then, as Dave later told me, he was so discouraged by the lack of fossils that he assumed this would be his first and last field season in Germany. I should mention that Stuart had previously uncovered a few small vertebrae, but because the vertebrae resembled an animal described from the Bromacker in 1991, the team was not very excited about the discovery. They couldn’t have been more wrong in their field identification of the vertebrae, however, but more on that in a later post.

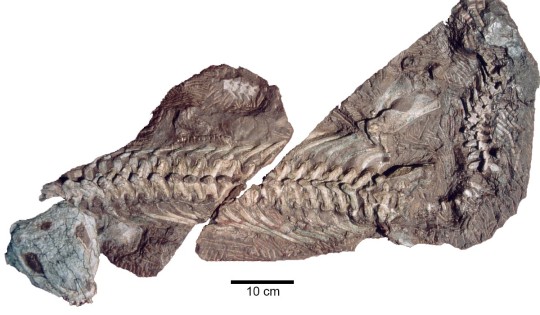

The team’s collective attitude changed when Stuart knocked off a chunk of bone-bearing rock from a bench in the quarry corner while shoveling away rock rubble. Careful examination of the fragment revealed part of the top of a roughly five-inch-long skull. We have since joked that Stuart gave it a lobotomy. While collecting the large block of rock containing the remainder of the skull, another piece of rock popped off the the edge of the block adjacent to the quarry wall. This piece had vertebrae in it. The team then realized that only the front portion of the animal was in the block freed from the quarry. The rest of the fossil skeleton remained in the quarry wall. Thomas later excavated the rest of the specimen and shipped it separately to Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH).

You can watch Dave and Stuart excavate the fossil-bearing block by clicking on the video link at the end of this post.

Based on the shape of both the exposed teeth in the broken skull and the exposed vertebrae, Dave and Stuart were able to identify the fossil animal as the genus Diadectes. Thomas had already collected a juvenile skull and other bones of Diadectes before his collaboration with Dave, but the specimen discovered in 1993 was by far the most complete and best preserved.

Once my preparation of the specimen was completed, which took a little over a year, Dave, Stuart, and Thomas begin their detailed study and description of the fossil. They determined that it represented a new species, which they named Diadectes absitus. “Absitus” is Latin for distant or far, in reference to the species being the first occurrence of Diadectes outside of North America. The generic name Diadectes was coined in 1878 by the famous paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope, and is a combination of the Greek “dia,” meaning crosswise, and “dēktēs,” meaning biter, in reference to its broad teeth. Other species of Diadectes occur in similar-aged rocks in the American southwest, and a few specimens are known from the Tri-State area of Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia.

Diadectes is a member of the group Diadectomorpha, which has oscillated between being considered a member of Amphibia or Amniota. Amphibians lay their eggs in water, which then hatch into tadpoles that later undergo metamorphosis. Today this group includes frogs, salamanders, and caecilians (limbless, worm-like burrowing amphibians). In contrast, amniotes either lay their eggs on land, like reptiles and birds do today, or the embryo develops sufficiently in the mother for live birth, as in most mammals. Except in rare cases, the type of developmental pathways of fossil animals cannot be determined because they are rarely preserved with their eggs or fetuses. Paleontologists instead study a variety of preserved features to determine group membership. As an example, amphibians typically have four fingers, whereas amniotes generally possess five.

Diadectes and its close relatives were herbivorous, that is, they ate plants. Their spatulate, incisor-like front teeth project forwards and were adapted for cropping vegetation. Longitudinal, parallel striations on their broad cheek teeth suggest that Diadectes could move its lower jaw fore and aft to grind plant matter against its upper jaw teeth, a motion called propalinal.

The presence of an enlarged torso and teeth adapted for grinding tough vegetation are evidence that Diadectes absitus likely consumed a diet of high-fiber plants. Animals that eat high fiber plants, such as cows, have enlarged torsos framed by a rounded rib cage to hold large guts for processing plant cellulose through fermentation by microorganisms.

Diadectes absitus lived at a time when herbivores were just beginning to evolve. One of the oldest known herbivores is the diadectomorph Desmatodon hollandi, which lived about 305 million years ago, whereas Diadectes absitus lived roughly 290 million years ago. We discovered a surprisingly high number of herbivores at the Bromacker.

A cast of the skeleton of Diadectes absitus is exhibited in the Fossil Frontiers display case in the Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition. Be sure to look for these once the museum re-opens. And stay tuned for my next post, which features another diadectomorph, Orobates pabsti.

Dave and Stuart excavate the fossil-bearing block (video)

Amy Henrici is Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Keep Reading

The Bromacker Fossil Project Part V: Orobates pabsti, Pabst’s Mountain Walker